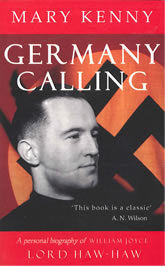

A personal biography of Lord Haw-Haw, William Joyce

A personal biography of Lord Haw-Haw, William Joyce

Published in hardback in October 2003. Revised paperback edition September 2004.

“Germany Calling is a triumph of enquiry.” Books Ireland.

“An absorbingly elegant study.” The Guardian.

“A convincing and gripping biography.” Sunday Independent.

“This is the most thorough study of Joyce’s personal life that is likely to be written.” London Review of Books.

“This book is a classic.” A.N. Wilson in the London Evening Standard.

“A fascinating account of a nasty, short and brutish life.” Jewish Chronicle.

“A very readable and thoughtful account.” Daily Telegraph.

AN INTRODUCTION

GERMANY CALLING – a personal biography of Lord Haw-Haw, William Joyce. Published in hardback in October 2003. Revisded paperback edition September 2004.

Lord Haw-Haw: From the Introduction “A queer little Irish peasant who had gone to some pains to make the worst of himself.” Rebecca West’s impression of “Lord Haw-Haw” in the dock: The Meaning of Treason.

Most biographies are, almost by definition, about successful people. This story is about a man who was a failure, who made the wrong choices at almost every point in his life, and ended his days on the gallows – with the negative distinction of being the last man, ever, to be hanged for High Treason by the British Crown.

William Joyce, who came to be immortalised as “Lord Haw-Haw” was born in America of English-Irish parents, grew up in Galway in the West of Ireland, became a fierce British patriot when he came to England and then embraced Nazi Germany in 1939. His sense of national allegiance was a little crazy and mixed-up, to say the least.

* * * * *

A biographer must have some sympathy with her subject, and even perhaps some sense of identification. I was first attracted to the idea of writing about William Joyce because I have experienced some of that mixed loyalty of being between England and Ireland: and some understanding of being between Catholic and Protestant values. I think of myself as thoroughly Irish, but I am married to an Englishman, and I have lived much of my adult life in England. I am a Catholic, but I spent much of my childhood with an aunt who had come from an Irish Protestant background, and some of those attitudes of the Irish Protestant ascendency formed part of my early influences.

William’s English-Irish mixture was in a different combination: his father was an Irish Catholic, and his mother a Lancashire Protestant – but a Protestant whose own father had been born in Ireland and had claimed kinship with the Ulster Brookes. William was not only half an Irishman: he also regarded himself as quarter an Ulsterman – my English husband suggested, at one point, that I call this biography “Hitler’s Orangeman”, a very Williamish provocation. Joyce inherited not only the volatile Celtic extremism (as a British secret intelligence report on William Joyce perceptively noted in the 1930s) but also an Orange fanaticism. No one loves the British Empire like an Ulster Loyalist, but no one can hate the English like an Ulsterman who has been disappointed by Mother England.

I chose William Joyce as a subject for a biography because I thought that this English-Irish, Catholic-Protestant identity was something I would understand, historically. But as time went by I began to have the slightly eerie feeling that I had not chosen William Joyce: William Joyce had chosen me. It would be fey to claim that I was being directed from beyond the grave by the ghost of Lord Haw-Haw, but I did come to be familiar with his spirit, and I did come to feel that some of my own mixed-up loyalties formed a link, over the years, with this perverse character. More eerily, I began to notice certain uncomfortable similarities between himself and myself.

With William’s youthful crazy habits, I could also identify. Like him, nothing pleased me more than smoking, drinking, talking, debating and arguing into the night, or indeed sitting up all night bashing a typewriter to meet a deadline. In this, he was in his element: this, and ranting from a platform, and curiously, reading aloud from James Joyce. My collaborator James Clark once happened upon William Joyce in a studio at the Berlin Rundfunkhaus, and himself reading aloud from Finnegans Wake, in the passage about “Anna Livia Plurabella”, (a lyrical text about the rather brackish River Liffey that runs through Dublin.) James Clark was startled. Finnegans Wake is a famously difficult book, full of nonsense words: but when read by an inspired voice, the whole thing somehow makes music. At that moment, James Clark said, he understood the point of Finnegans Wake, and saw, in William Joyce, the Joycean.

William Joyce had something in common with James Joyce: both formed by a Jesuit education, both of whom had something of the “jesuit strain …….injected the wrong way”; both connected with Galway, both indulged eldest sons with a devoted younger brother, both fascinated by philology, word-play, puns, the inter-textuality of Latin phrases interspersed with English, and both fixated on Jewishness – James philo-Semitic, William anti-Semitic.

* * * * *

William Joyce was not a particularly nice man; and when he was bad he was horrid. The most disagreable streak in his personality was his pathological anti-Semitism, which was, as the Irish say, beyond the beyonds. If you said to Willliam, “It’s rainey, today, isn’t it?” he would reply, “Yes, and don’t you know the Jews make all the umbrellas, and have a world monopoly in umbrellas, and are using the umbrella market to further their fiendish Communist Plot of International Finance.” I have come to understand, I think, the source of this fixation, which I explain in the course of the text, but I would not go so far as to say that “tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner”. I don’t think he should be pardoned for this, particularly in 1945, after the war, when the Nazi concentration camps were being opened up and he showed no scant remorse about the consequences of hate crime.

It has to be said that there was nothing unusual in anti-Semitism during the 1930s. It was to be found in the work of Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot and George Orwell, the popular writing of John Buchan, Dornford Yates and Agatha Christie; it can be found in W.B. Yeats, and one of William Joyce’s most ferocious admirers who almost outdid him in anti-Jewish feeling was the poet and mentor of poets, Ezra Pound. There was a certain element of joking anti-Semitism in the pre-war (but not post-war) lyrics of Noel Coward and it was evident in the essays of Wyndham Lewis. It appears in the amusing diaries of “Chips” Channon, the journalism of Beverley Nichols, the industrial philosophy of Henry Ford, in the eugenic texts of Karl Pearson and in the attitudes of the co-founder of the New Statesman, the Fabian Sydney Webb, who at least even-handedly thought that both the Irish and the Jews were unfit to breed.

Anti-Semitism was also commonplace among ordinary people, as shown in the Home Intelligence Reports – British Government monitors of what people in 13 regions around the United Kingdom were talking about during the war. Throughout the Second World War, grumbling about the Jews either for allegedly running a black market or seeming too “ostentatious” in their lifestyle was a much-repeated theme. So although William’s anti- Semitism was unpardonable, it was but an inflated and possibly pathological amplification of a prejudice that many people shared. We must also remember that various racial and group prejudices were commonplace in the recent past: right up until the 1960s, English landladies plying for trade hung a “No Irish” sign in their front windows, sometimes with the variation, “No Irish, No Coloured”.

We know that Anti-Semitism is odious because we know the deepest pit of evil to which it led; but I also came to the view, in the time I spent with the ghost of William Joyce, that it is also unlucky. Not because there is a world conspiracy of Jews monopolising the media and controlling everything from governments to finance, as William and his colleague John Beckett believed: but because anti-Semitism produces in the individual a negative energy which burns away at all positive gifts and positive talents, and eventually consumes the good karma.

And William Joyce did have good qualities, and interesting ideas, which have been annulled or overlooked by the flare of his violent hatreds. His political ideas were not all loathsome: some of his precepts about education could be endorsed, without alteration, by the most liberal-minded progressives of our day. He favoured much more equality in education: and much more emphasis on making children happy. His economic ideas about Ireland’s woes were very sensible: he thought what Ireland needed was lots money invested in it, which has turned out to be exact.

On a personal level, William had some of the attractive qualities of the absent-minded professor: he had no interest in possessions – he only ever wanted wine, cigarettes, books and a few opera records – and always looked a bit of a mess. He was mechanically incompetent, couldn’t ride a bicycle, dance or play games. He could speak on the radio but could “barely succeed in receiving a powerful station on the wireless and could never get the tuning really right”, according to his friend John Angus Macnab. While he greatly irritated some people, he commanded the lifelong loyalty of close friends. He could be very good company when he was on form, and his friends sometimes saw William in unusual moods of mildness and even humility: “when he put aside his jackboots”, said Chesterton, he could emerge “as a humble person, not without charm and with a delicate sense of irony”. He eventually faced his own execution with equanimity.

William Joyce did nearly everything wrong in his life, and certainly had some dreadful views; but he was not without redeeming qualities. Then, none of us are.

Buy Germany Calling or any other of Mary’s books from her publisher. The ISBN for “Germany Calling” is 1902602781.

Cost: €25

ebooks can be purchased :

Kindle – amazon.com

Kindle – amazon.co.uk

ebook – Kobo