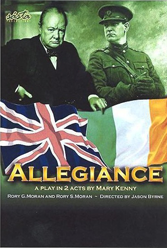

A play about Michael Collins and Winston Churchill

A play about Michael Collins and Winston Churchill

Background & Context

In 1921, the Irish rebel leader Michael Collins was ordered to travel to London – with Arthur Griffith and the Irish delegation – to negotiate the Anglo-Irish Treaty which followed the Truce and the War of Independence. Collins loathed the assignment and protested vehemently: but the Irish political leader Eamon de Valera insisted that he must go.

In London, Collins was regarded, at this time, in Winston Churchill’s own words, as “a legend among the gunmen and revolutionaries who held Ireland in thrall… [whose] prestige and influence amongst all extremists was high.” Churchill was Colonial Secretary in charge of Ireland, and the two men were prepared to detest one another across the green baize table. Churchill was deeply opposed to Irish “rebellion”: Collins certainly did not trust Winston, who had been part of a British government which had sent the notorious “Black and Tans” to Ireland.

Yet, at a point when the Treaty talks seemed to be in stasis, Churchill and Collins spent the whole night drinking together, talking, arguing, even singing and reciting poetry to one another. They emerged from this session, according to Lord Birkenhead “fascinated” by each another: and according to another witness, as “bosom friends”. Bosom friendship is an exaggeration, but some chord was touched, emotionally, between the two men. Men who do not agree with one another can nonetheless harbour a quixotic liking or admiration: Churchill always admired a warrior, and Collins knew that, somehow, he had to learn the art of politics rather than fighting.

Moreover, after this, Churchill softened towards Ireland, and gave Collins and the nascent Irish Free State every support he could. For his part, Michael Collins, just before his untimely death, sent a valedictory message: “Tell Winston we could never have done it [establish the Free State] without him.”

The play is an imaginative reconstruction of how the encounter between the two might have progressed, drawing on historical sources. It is about Anglo-Relations relations at a crucial point in our history; it is about two very charismatic historical characters, republican and imperialist: and it is about something which must continue to be done in our world – when political negotiation has to arise out of conflict.

Book Shops and Individuals can buy the Collins-Churchill text directly by contacting Mary directly on

mary@mary-kenny.com.

Also available by post at

Kildare Street Books

P.O. Box 10073

Dublin 2

ISBN of ‘Allegiance’ is 0-9550167-0-3

jacket design by Anthony Carey

Performance and Reviews

Allegiance was first given a public reading in Dublin, at the New Theatre, and subsequently in London, unusually, at the Reform Club, where it was well-received – even reviewed, in the London Independent newspaper. With Mel Smith as Churchill and Irish actor Brendan Coyle as Collins, the Independent critic Roderick Dunnett wrote on 20 September 2005: “Staged as a one-off in a cut version that works staggeringly well and directed with masterly economy by Brian Gilbert, Allegiance is a witty reimagining of the canny duelling and curt repartee that led Churchill and Collins to metamorphose almost overnight from bitter foes to sparring partners to bosom pals. Sly, wily, subtle – and cryptic….Smith is a sensational Churchill: this was no puny parody. His and Coyle’s perfect pacing mirrored Kenny’s finely mapped medley of shifting emotions.”

The play went to the Edinburgh Festival in the summer of 2006, where advance publicity regarded it as one of the highlights of the theatre festival, previewed as such by the London Sunday Times and The Scotsman. The role of Michael Collins was now taken over by the brilliant young Irish actor, Michael Fassbender, while Mel Smith continued with his remarkable Churchill. (Scotland had recently banned smoking in public places, and a certain notoriety occurred when Mel came near to breaking the law by lighting up the famous Churchillian cigar on stage: the Edinburgh authorities threatened to close down the theatre – the Assembly Rooms – for the entire festival if he did so. He desisted just in time, but it became a news sensation, and a talking-point about the role of naturalism on stage – although some critics complained – notably in the Financial Times – that the sensation slightly took the focus off the play.)

The Edinburgh reviews were warmly favourable to the play and the performances. The Guardian critic Lyn Gardner wrote that “This play asks serious and interesting questions. Where is history really made? How are negotiations and treaties really thrashed out? How far do the personal lives of politicians affect the decisions they make and the deals they broker? Writer Mary Kenny goes at these questions hammer and tongs in a scenario that imagines what might have happened in a private meeting between the two men. Churchill, scion of the aristocracy, still believes in the Empire as ‘one of the great civilising missions of the world’. Collins, cast as a romantic hero by the British press, is lean, hungry and wolfish. These are men who inhabit not just different worlds but different universes, and the stage is set for a showdown between British imperialism and Irish nationalism.

“Yet Kenny suggests that even those on opposite sides of the negotiating table can discover common ground if they recognise the humanity in each other. Poetry brings them together …and grief bonds them in a relationship that has a touch of the father-and-son about it – and which also seals Collins’ fate. Michael Fassbender and Mel Smith are excellent, the latter all jowls and petulant lower lip so that he resembles a very clever baby. No smoke, but plenty of fire.” (The Guardian 10 August 2006.)

The Times called the play “A discussion as plausible as it is absorbing ….pretty pertinent today. The wishfulness in the play doesn’t turn into sentimentality. Indeed, Kenny uses the meeting to suggest that personal rapport can lead to political breakthroughs, and to ask questions about the difference between terrorists and freedom fighters.” (The Times 8 August 2006). In the Daily Mail theatre critic Quentin Letts described the play “an interesting and touching work. The historical validity is for others to judge, but this is a warm portrait of the two men…Mary Kenny has written an intriguing vignette. Both men knew what it was to be hunted – Churchill (by the Boers) and Collins (by the British). Both were killers, be it in mortal combat or in leading soldiers to their deaths. Both, against their instincts, recognised that a way had to be sought between the ‘chivalric code’ of formal warfare and the ‘sniper’s law’ of terrorism.” (Daily Mail, 11 August 2006.) In the Daily Telegraph critic Dominic Cavendish wrote: “Smith’s portrayal of the great man might be his finest hour yet: jowls and lips quivering under the weight of solemn pronouncements, his stooped Churchill has the monumental quality of a statue. Yet, always, even at his most sedentary, we see a mind at work, ceding nothing in the mocking, tit-for-tat exchanges about the deadly toll of imperialism and resistance, yet looking for points of connection – a poem here, a reminiscence there. When Churchill blubs at the memory of his deceased youngest daughter and Michael Fassbender’s Collins, initially cold and formal, puts his hand on his soulder, you grasp how close the two men have become.”

The London Independent’s reviewer, Lynne Walker, called Allegiance “a keenly imagined script” and “an absorbing entertainment”. “Fassbender endows Collins with a magnetism and quite intelligence, his forecasting of his death taking on a real poignancy….Whatever unlikely alliance this encounter helped Churchill and Collins to form in the midst of these secret negotiations over the Irish question, Smith and Fassbender convey the increasingly warm relationship between the two men…” It was also reviewed favourably in the Financial Times (although the critic said the smoking controversy was too much of a distraction from the work); while The Scotsman’s critic Joyce McMillan wrote: “It’s difficult not to be moved by the sense of profound historic intimacy between the two ancient enemies evoked by the growing friendship between the two men. And when Collins reaches for compromise with the British, knowing that he will probably pay with his life, the heart aches for the plight of peace-making leaders through history; the ones who have risked the terrible and emotive charge of treachery, in order to free their people from war.” (The Scotsman 10 August 2006.) The whole ensemble, she judged, “makes for riveting theatre…so full of heavily charged topical relevance.”

Allegiance was a lead review in all the main newspapers, and played to full houses.

A transfer to the London stage was planned, but contractual problems arose in 2007-8. Yet Mel Smith has said recently that he hopes to bring it to London in the near future – he “adored” the play, he told an interviewer in the magazine Time Out (issue of 25 June-1 July 2009).

* * * * *

Mary Kenny’s play, in script form has attracted plaudits from a wide range of readers. Ben Barnes, the former Artistic Director of Ireland’s national theatre, the Abbey, said of it: “Allegiance is very informative and engaging: I particularly liked the scenes between Collins and Churchill which were incisive and at the same time tinged with poignancy when viewed with the hindsight of subsequent history.”

Professor Roy Foster, professor of Irish history at Oxford, wrote: “I read Allegiance and liked the way the arguments were presented through two very convincingly recaptured ‘voices’ – which also help to restore the contemporary dimension to arguments usually approached with the advantage of hindsight.”

And Senator Nora Owen, grand-niece of Michael Collins and a former Irish Minister for Justice wrote: “Mary Kenny’s writing has opened up a rarely examined human aspect of Collins’ role during the Treaty negotiations. I had often heard of the bond that grew between Churchill and Collins during the talks, and Mary has now brought this to life in her play. Congratulations on an innovative and perceptive piece of writing which will add to people’s knowledge and admiration of Michael Collins.”

Corin Redgrave, the actor, called the play – “A very moving portrait of two men who were antagonists yet, at a certain level, comrades, almost, because both had a love of something larger than political advantage, and each recognised that quality in the other.”

The author especially appreciates a response sent by Mr Terry Corrigan, whose grandfather served with Michael Collins: “Sublime. Absolutely sublime. I read it in one sitting and then read it all over again. Never have I witnessed the transition of historic ghosts, to breathing, sweating mortals sculpted with such aplomb. I will read it again and again and will urge others to do the same.

“My Grandfather served with the Big Fellow, and played no small part in dispatching the infamous Cairo Gang.. It gives me a sense of what the struggle entailed, and how the pen that signs the truce is by association, also fuelled with blood. But.. Erin Go Bragh Mary.”